NTSB Probable Cause Report Also Cites 'Inherent Limitations' Of 'See-And-Avoid'

The NTSB has issued its probable cause report from a mid-air collision on August 16, 2015 that fatally injured five people on board two aircraft. In the report, the board indicts the concept of "see-and-avoid", which is at the core of much of our flying.

According to the report, a Cessna 172 (N1285U) was conducting touch-and-go landings at Brown Field Municipal Airport (SDM), San Diego, California, and the experimental North American Rockwell NA265- 60SC Sabreliner (N442RM, call sign Eagle1) was returning to SDM from a mission flight. SDM has two parallel runways, 8R/26L and 8L/26R; it is common in west operations for controllers to use a right traffic pattern for both runways 26R and 26L due to the proximity of Tijuana Airport, Tijuana, Mexico, to the south of SDM.

On the morning of the accident, the air traffic control tower (ATCT) at SDM had both control positions (local and ground control) in the tower combined at the local control position, which was staffed by a local controller (LC)/controller-in-charge, who was conducting on-the-job training with a developmental controller (LC trainee). The LC trainee was transmitting control instructions for all operations; however, the LC was monitoring the LC trainee's actions and was responsible for all activity at that position.

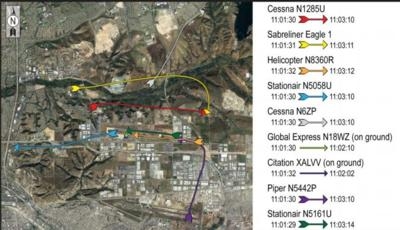

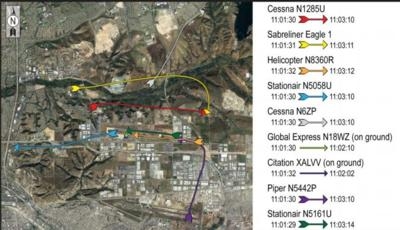

About 13 minutes before the accident, the N1285U pilot contacted the ATCT and requested touch-and-go landings in the visual flight rules (VFR) traffic pattern. About that time, another Cessna 172 (N6ZP) and a helicopter (N8360R) were conducting operations in the VFR traffic pattern, and a Cessna 206 Stationair (N5058U) was inbound for landing. Over the next 5 minutes, traffic increased, with two additional aircraft inbound for landing. (Figure 1 in the factual report for this accident shows the aircraft in the SDM traffic pattern about 8 minutes before the accident.)

The LC trainee cleared the N1285U pilot for a touch-and-go on runway 26R; the pilot acknowledged the clearance and then advised the LC trainee that he was going to go around. The LC trainee advised the N1285U pilot to expect runway 26L on the next approach. At that time, three aircraft were using runway 26R (Global Express [N18WZ] was inbound for landing, N6ZP was on a right base for a touch-and-go, and a Cessna Citation [XALVV] was on short final) and three aircraft were using runway 26L (N1285U was turning right downwind for the touch-and-go, a Skybolt [N81962] was on a left downwind for landing, and N8360R was conducting a touch-and-go landing). After N1285U completed the touch-and-go on runway 26L, the pilot entered a right downwind for runway 26R. Meanwhile, Eagle1 was 9 miles west of the airport and requested a full-stop landing; the LC trainee instructed the Eagle1 flight crew to enter a right downwind for runway 26R at or above an altitude of 2,000 ft mean sea level. At this time, about 3

minutes before the accident, the qualified LC terminated the LC trainee's training and took over control of radio communications. From this time until the collision occurred, the LC was controlling nine aircraft.

During the next 2 minutes, the LC made several errors. For example, after N6ZP completed a touch-and-go on runway 26R, the pilot requested a right downwind departure from the area, which the LC initially failed to acknowledge. The LC also instructed the N5058U pilot, who had been holding short of runway 26L, that he was cleared for takeoff from runway 26R. Both errors were corrected. In addition, the LC instructed the helicopter pilot to "listen up. turn crosswind" before correcting the instruction 4 seconds later to "turn base."

About 1 minute before the collision, the Eagle1 flight crew reported on downwind midfield and stated that they had traffic to the left and right in sight. At that time, N1285U was to Eagle1's right, between Eagle1 and the tower, and established on a right downwind about 500 ft below Eagle1's position. N6ZP was about 1 mile forward and to the left of Eagle1, heading northeast and departing the area. Mistakenly identifying the Cessna to the right of Eagle1 as N6ZP, the LC instructed the N6ZP pilot to make a right 360° turn to rejoin the downwind when, in fact, N1285U was the airplane to the right of Eagle1. (The LC stated in a postaccident interview that he thought the turn would resolve the conflict with Eagle1 and would help the Cessna avoid Eagle1's wake turbulence.)

The N6ZP pilot acknowledged the LC's instruction and began turning; N1285U continued its approach to runway 26R. However, the LC never visually confirmed that the Cessna to Eagle1's right (N1285U) was making the 360° turn. Ten seconds later, the LC instructed the Eagle1 flight crew to turn base and land on runway 26R, which put the accident airplanes on a collision course. The LC looked to ensure that Eagle1 was turning as instructed and noticed that the Cessna on the right downwind (which he still mistakenly identified as N6ZP) had not begun the 360° turn that he had issued. The LC called the N6ZP pilot, and the pilot responded that he was turning. In the first communication between the LC and the N1285U pilot (and the first between the controllers in the ATCT and that airplane's pilot in almost 6 minutes), the LC transmitted the call sign of N1285U, which the pilot acknowledged. N1285U and Eagle1 collided as the LC tried to verify N1285U's position. A postaccident examination of both

airplanes did not reveal any mechanical anomalies that would have prevented the airplanes from maneuvering to avoid an impact.

In a postaccident interview, the LC stated that his personal limit for handling aircraft was four aircraft on runway 26R plus three aircraft on runway 26L (for a total of seven). From the time the LC took over local control communications from the LC trainee (3 minutes before the accident) until the time of the collision, the LC was in control of nine aircraft. Thus, the LC had exceeded his own stated workload limit. Research indicates that the cognitive effects of increasing workload may include memory deficits; distraction; narrowing of attention; decreased situational awareness; and increased errors, such as readback errors or giving instructions to the wrong aircraft. (Mica Endsley and Mark Rodgers's 1997 report, Distribution of Attention, Situation Awareness, and Workload in a Passive Air Traffic Control Task: Implications for Operational Errors and Automation [FAA Report No. DOT/FAA/AM-97/13], details the cognitive effects of increasing workload.) To resolve the increasing workload, the LC had

two options. He could have directed traffic away from SDM or split the local control/ground control positions, but he did neither. The LC trainee was qualified to work the ground control position, and the SDM ATCT had three controllers in the facility, which was the normal staffing schedule for that day and time.

As a result of the high workload, the LC made several errors after taking over the position from the LC trainee, including not responding promptly to a departure request from the N6ZP pilot and incorrectly instructing a helicopter pilot to turn to crosswind before correcting the instruction to turn base. The LC also did not provide traffic and/or sequence information with the instructions for the N6ZP pilot to turn 360° right. If the LC had done so, the N6ZP pilot might have reminded the controller that he was departing the airspace or requested clarification per 14 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 91.123(a), "Compliance with ATC [Air Traffic Control] Clearances and Instructions." In addition, if the Eagle1 flight crew had heard their aircraft called as traffic to another aircraft, it may have helped their visual search or prompted them to seek more information about the location of the conflicting traffic. The LC's stress amid the high workload was evidenced in his "listen up. turn crosswind"

instruction to the helicopter pilot, after which the Eagle1 cockpit voice recorder (CVR) recorded the pilot comment, "wowww. he's like panicking" (with an emphasis on "panicking").

Most importantly, the LC misidentified N1285U as N6ZP and did not ensure that the Cessna to the right of Eagle1 was performing the 360° turn before issuing the turn instruction to Eagle1. Although the N6ZP pilot had already requested a departure from the area and the LC had approved the departure request, the LC still believed that N6ZP was to the right of Eagle1, which indicates that the LC lacked a full and accurate mental model of the situation once he took over communications from the LC trainee. The LC trainee stated in a postaccident interview that when the Cessna on the right did not start the right turn, he suggested to the LC that the intended aircraft may have been N1285U. The high workload due to the increased traffic likely contributed to the LC's incomplete situational awareness.

In a postaccident interview, the LC reported that, at the time that he took over for the LC trainee, he had four issues to resolve, one of which was the potential conflict between Eagle1 and the Cessna on the right. Thus, he was aware of the potential conflict between two aircraft, even though he did not have the accurate mental picture of which Cessna was which. The LC explained that the acknowledgement from the N6ZP pilot of the right 360° turn to rejoin the downwind indicated to him that the intended Cessna pilot to Eagle1's right had received and acknowledged his instructions. Had he looked up to ensure that the control instructions that he provided to the Cessna on the right were being performed, he would have noticed that the Cessna to the right of Eagle1 was not turning and likely would not have issued the conflicting turn instruction to Eagle1.

The board's aircraft performance and cockpit visibility study determined that once Eagle1 began the turn to base leg, Eagle1 would have been largely obscured from the N1285U pilot's field of view but that N1285U should have remained in the Eagle1 pilots' field of view until about 4 seconds before the collision. It is likely that, as N1285U neared the end of the downwind leg (after Eagle1 overtook N1285U from behind and to the left), the pilot was anticipating his turn to the base leg and that his primary external visual scan was to the right, toward the airport, instead of to the left where Eagle1 was. Although the pilot may have had some cues of Eagle1's relative positioning in the pattern based on his monitoring of the ATCT communications, the challenge remained of detecting the airplane visually while maneuvering in the pattern.

Although the N1285U and Eagle1 pilots were responsible for seeing and avoiding the other aircraft in the traffic pattern, the aircraft performance and cockpit visibility study revealed that their fields of view were limited and partially obscured at times. Research indicates that any mechanism to augment and focus a pilot's visual search can enhance their ability to visually acquire traffic.

The National Transportation Safety Board determined the probable cause(s) of this accident to be the local controller's (LC) failure to properly identify the aircraft in the pattern and to ensure control instructions provided to the intended Cessna on downwind were being performed before turning Eagle1 into its path for landing. Contributing to the LC's actions was his incomplete situational awareness when he took over communications from the LC trainee due to the high workload at the time of the accident. Contributing to the accident were the inherent limitations of the see-and-avoid concept, resulting in the inability of the pilots involved to take evasive action in time to avert the collision.

(Images provided by the NTSB)

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (04.24.24): Runway Lead-in Light System

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (04.24.24): Runway Lead-in Light System ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (04.24.24)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (04.24.24) Aero-FAQ: Dave Juwel's Aviation Marketing Stories -- ITBOA BNITBOB

Aero-FAQ: Dave Juwel's Aviation Marketing Stories -- ITBOA BNITBOB Classic Aero-TV: Best Seat in The House -- 'Inside' The AeroShell Aerobatic Team

Classic Aero-TV: Best Seat in The House -- 'Inside' The AeroShell Aerobatic Team Airborne Affordable Flyers 04.18.24: CarbonCub UL, Fisher, Affordable Flyer Expo

Airborne Affordable Flyers 04.18.24: CarbonCub UL, Fisher, Affordable Flyer Expo