Looking At The End Of America’s Manned Lunar Program

By Wes Oleszewski

(Editor's Note. Unproofed copy of this story was originally posted Monday. We apologize for the error)

On the 40th anniversary of the Apollo 16 launch, it is important to look at where we were as a space-faring nation at the time of that mission and perhaps consider where we are as a space-faring nation today. For the purposes of looking back we will gaze through the eyes of a rabid, spaceflight crazed eighth-grader in the year 1972… me.

Through the autumn of 1971 I had been counting the days to the scheduled launch date. Then, however, for the first time in the history of manned Apollo launches there was a delay in the launch due to a hardware failure. The Apollo 16 vehicle had been rolled out to launch Complex 39A on the 13th day of December, 1971 for a scheduled launch date of March 17, 1972. But, in the first week of January, 1972 a helium pressure test ruptured a Teflon bladder in one of the command module’s reaction control system fuel tanks. On January 7th NASA announced that the problem would require a rollback to the VAB which would delay the launch for at least a month. Exactly 20 days after that announcement a flight-rated Saturn V was rolled back to the VAB for the first time. Repair of the fuel tank required that the command module had to be de-mated from the stack and opened to separate the heat shield from the upper command module in order to permit access to the fuel tank. Once all that was accomplished the

spacecraft was re-stacked and Apollo 16 once again rolled out Pad 39A. A new launch date was set for Sunday, April 16, at 12:54 pm. This little delay was to work out in an unexpected yet favorable way for me, the space-crazed eighth-grader.

As the launch day grew near I was determined to be much more prepared to record Apollo 16's audio from the television then I had been for Apollo 15. This time I had a brand-new cassette tape recorder that I had gotten for Christmas after having run the cassette player that I had "borrowed" from my younger sister and worked to death, (a wrong which, to this day, she has never forgiven me for, but I'm sure one day she may work it out in therapy somewhere.) I had adapted a small tripod from an old telescope and a wooden school ruler to hold the tape recorder’s microphone at a measured distance from the family TV’s speaker. In this the era prior to cable TV being commonplace, I had to run audio checks on each channel of the three television networks that we received over the airwaves in order to discover which one presented the least 60hz hum in the audio recording. Additionally, I dragged my black-and-white portable TV into the living room to augment the family TV. That, however, brought to

light my greatest problem for the launch itself; the family. Since launch day was scheduled on the weekend there was the issue of the entire family "living" in the "living room" while I was trying to record. The background noise, the chatter, the inane questions directed at me as well as the TV would all be superimposed onto the tape recording that I intended to keep and play forever. I, however, lucked out as my problem was solved in the early hours of Sunday morning when my younger brother awakened with symptoms of an appendicitis. He had to be rushed to the hospital. As they got ready to leave, mom looked at me and pointlessly asked, "Are you going too?" but instinctively I think she knew better. “GO?” To sit in some hospital waiting room? On the day of the Apollo 16 launch!?!... I think not! As they left she remarked that they would call me and let me know how little brother was doing. I responded by saying "Okay, just don't call between noon and two, because I'll be recording the

launch." Now it would be just me, the TV, the tape recorder, my 1/200 AMT Saturn V model and Apollo 16- all alone for launch day. Other than being at KSC in person, it was an eighth grade space-buff’s dream. The delay of the launch back in December had placed the launch on exactly the right day for me.

My audio test had shown that WNEM, TV5 presented the best sound quality. They were an NBC affiliate and thus, launch coverage began at noon hosted by John Chancellor. On my backup TV set was spaceflight icon Walter Cronkite with CBS coverage on UHF channel 25 WEYI. The countdown was progressing far more smoothly than NBC’s launch coverage, as after Chancellor's prerecorded opening monologue the live coverage picked up, but had no sound. On the picture images flashed of the host and the sound technician scrambling with lines trying to recover the audio. Coverage was hastily switched to New York where Garrick Utley filled in until the audio was restored. At KSC only two issues had cropped up in the launch vehicle’s final hours of countdown. Early in the morning a glitch had been detected in a backup yaw gyro. This was later determined to be an issue that the controllers felt they could live with and the countdown was allowed to continue. Then, at the T-51 minute point in the count, there was

a breakdown in the transmission of telemetry between the Goddard Center and a main releasing station in Monrovia, West Africa. That glitch was bypassed through the use of backup equipment and the count proceeded.

In spaceflight coverage of this era no one reporting seemed to be able to resist an opportunity to drive home the point of how “expensive” the Apollo program was. When opening stories on the evening news about Apollo 16 the networks routinely prefaced the story by stating the cost of the Apollo program, or the cost of Apollo 16 itself. For example, during the preflight broadcast the standard, stock film of the astronauts eating breakfast and suiting up was shown. John Chancellor in narrating that film said, "Here's Young suiting up, complicated business getting into those terribly expensive suits…" As if it would be preferable for astronauts walking on the surface of the moon to be in "cheap" suits. But 1972 was a time when the media and pop culture were pressing every opportunity to convince the masses that flying to the moon was pointless, boring and insanely expensive. Of course it was also a time when Americans were annually spending more on cigarettes than it cost to operate

the Apollo 16 flight.

Out on Pad 39A, at 8.9 seconds in the count the automatic sequencer ignited four pyrotechnic devices in each of the first stage’s F-1 engines. This started the chain of events that would feed fuel to the engines and bring the Saturn V to life. Moments later a signal to a solenoid opened the main LOX valves and the power and the glory of the Saturn V erupted. For those of you reading this who were born after the era of Apollo and never had the chance to witness a Saturn V launch either in person or on TV, the event is as difficult to describe to you as it will be for you to describe a shuttle launch to future generations. Unlike the shuttle, the Saturn V ignited and remained held down on the pad for nearly 9 seconds as billows of flame and smoke burst from the flame trench. Once the hold-downs released the vehicle took another 12 seconds just to clear the launch tower. Shock waves rolled across the distance and were so strong that they shook the buildings at the press site to the point where

ceiling tiles fell down and broadcast equipment was interfered with. On my TV sets it almost seemed as if the reverberations from the launch wanted to shake the furniture. The feeling was that of "we're going" as if the Saturn V was able to take everyone with it on a trip to the moon.

For 2 minutes and 42 seconds the S-I-C first stage plowed upward. Its raw power was necessary to punch through the lower in thicker areas of the Earth's atmosphere. After 162 seconds of flight the Saturn V was 221,304 feet in altitude and well above most of the Earth's atmosphere. It was essentially in a vacuum- it's job was done. Following the inboard engine’s cut off at 2 minutes and 10 seconds, the four giant F-1 outboard engines simultaneously shut down at 2 minutes 39.9 seconds. The Saturn V’s instrument unit (IU) then sent a signal to the S-I-C/S-II stage switch selectors which sequenced stage separation. The switch selectors sent a 28 volt DC impulse that actuated circuitry in the separation system to fire an exploding bridgewire and sequence the firing of a linear shaped charge that passed completely around the vehicle in the separation plane. When that charge was detonated a series of 199 tension straps around the vehicle’s circumference that held the two stages together

were severed. That action freed the S-I-C first stage from the S-II aft skirt and allowed the first stage to fall away. Six hundred milliseconds after the outboard engines are signaled to cutoff the IU signaled the eight retro rockets embedded in the S-I-C’s lower engine fairings to ignite in retrograde- aiding in the separation of the two stages. The retro rockets themselves each measured 86 inches long, 15.75 inches in diameter and weighed 504 pounds. The propellant was an ammonium perchlorate oxidizer in a polysulfide fuel binder with a grain having a 12 point star core and each rocket produced an average thrust of 86,600 pounds while burning for just .63 seconds. At retro rocket ignition the forward ends of the fairings was burned and blown through by the exhaust gases of each retro rocket. On board, the astronauts would see debris from this action “travelin’ along with us” for several minutes after staging. Interestingly the S-I-C stages would separate at approximately

230,000 feet of altitude yet continue to ascend to about 360,000 feet before arcing over to plunge engines-first into the ocean. It was a spectacular sight both in person and on television that will probably never be seen again. Of course, to an eighth grade space buff it all just looked like a really cool staging.

What none of us saw and few of us knew about the Saturn V’s first stage separation process was a scene that took place inside the command module at the moment of staging. Depicted accurately in the Hollywood movie "Apollo 13" the astronauts, although securely strapped in their seats were thrown violently forward against their harnesses and then slammed back into their couches. The crew of Apollo 8 were the first to experience the staging whiplash, but downplayed the event and allowed the crew of Apollo 9 find out for themselves. Whether intentional or not, that downplay of this startling event turned into a small "gotcha" for future crews. Astronaut Dave Scott, who was on the second crew to experience the staging event, later commanded Apollo 15, but never let on to his crew what to expect at S-I-C separation. So, when Apollo 15 staged, astronauts Jim Irwin and Al Worden were caught completely by surprise. On Apollo 16, commander John Young was kind enough to brief Charlie Duke and Ken Mattingly

about what to expect.

One interesting fact that a lot of people don't know about the Saturn Vs is that all of the engines used to send the vehicles aloft had already been fired in the test stand, often for a greater period of time than full flight duration. For example, S-I-C 11, which was used to boost Apollo 16 was test fired for 96 seconds in June 1969, but a fire on engine number three caused an abort cutoff. Engines number three and number five were replaced. One year later another test firing took place lasting 70.6 seconds adding up to a total stage-run of 166 seconds for engines number one, two and four- 6 seconds longer than flight duration. Likewise the second stage, S-II 11 was test fired in November 1969 four 371.6 seconds-28 seconds longer than flight duration. The exception was the Apollo 16 S-IVB third stage, number 511, which was tested in a 442.8 second test firing. In flight the S-IVB actually fired for a total of 564 seconds. Unlike the later Space Shuttle Main Engines, the Saturn V’s engines were

not normally completely torn down and inspected after such a test firing- they were simply shipped back to KSC tagged as ready to go. So, as Apollo 16’s S-I-C stage dropped away into the Atlantic Ocean and the S-II stage turned into a bright star in the afternoon sky the vehicle would press toward orbit on used, but reliable engines.

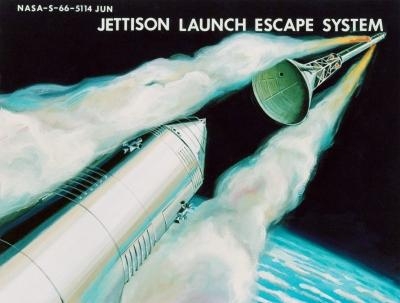

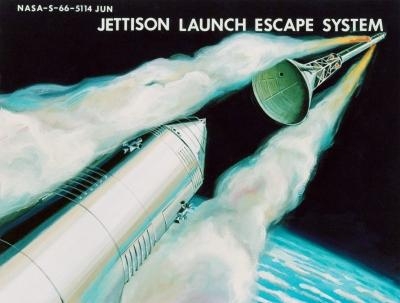

Squinting at my television set I watch the small white point of light that was Apollo 16 for as long as the news cameras would allow. Just 30 seconds after staging, the S-II second stage’s aft interstage skirt separated in a near-identical process to that which released the S-I-C stage. Jettison of the launch escape tower and the Boost Protective Cover was triggered by the IU 30 seconds and 36 seconds later respectively. For the first time in the flight the astronauts were able to look out of all of the command module's windows. On the TV I could see both the skirt and tower tumbling away in the fuzzy black-and-white images that were broadcast, but in doing so I left a series of nose prints on the picture tube.

While burning on the S-II, the Saturn V’s mission became one of velocity and fine-tuned guidance. The vehicle, now steered by its five J-2 engines, began to tilt down until its angle to the surface of the earth was less than 20 degrees. This allowed Apollo 16 to now trade rocket fuel for large increases in forward velocity. Additionally the IU now directed the five engines toward putting the vehicle on its preplanned trajectory into orbit. Shortly after the S-II began its work Apollo 16 was out of the range of ground cameras and the networks switched to the familiar animation that we space-buffs knew so well. Of course, they always had to put the word "animation" on the screen too. I always thought that this was in order to comply with the 1964 “People Watching TV Who Are Idiots Act."

On Apollo 16 the S-II stage did its job perfectly. At 7 minutes and 41 seconds into the flight the IU signaled the stage’s center engine to shut down. This is a procedure that was derived from the Apollo 13 launch when a longitudinal oscillation called "Pogo" had caused an engine to shut down prematurely. One solution to the Pogo problem was to simply program the stage to shut down the center engine early. Just under 1 minute later the vehicle was given the “level sense arm” command. This command armed a series of five probes that resided at the bottom of the fuel tank and LOX tank. As the fuel and oxidizer in the tanks was depleted eventually the probes would be uncovered. When any two probes in one tank were uncovered the shutdown of the remaining four engines would be triggered. Thus, at the 9 minute 17 second point the level sense triggered the shutdown of the S-II stage. Again a series of four retro rockets were used to separate the second stage from the third stage. After a

short 2 minute and 22 second burn Apollo 16 was in orbit. Later, on the second orbit, the Saturn’s S-IVB third stage was reignited and boosted Apollo 16 out of Earth orbit and onto a transmitter trajectory. For the eighth time in history humans were flying to the moon.

When I went to school the following day I found, not much to my surprise, that nearly all of my classmates had little or no idea that the launch had taken place. Most telling was the fact that neither my social studies teacher, nor my science teacher had bothered to watch the launch and actually seemed quite unaware that it had taken place. That was the way of things as the era of Apollo neared its end. Although across the world millions upon millions of people in Third World nations were glued to the mission by any means available to them, here in the United States, almost universally, Apollo 16 was taken for granted. Within the next eight months, as the final Apollo mission, Apollo 17 splashed down and America would take all that it had invested in Apollo and with barely a whimper from the American public, who would be reaping the harvest of benefits from the program in decades to come, would simply throw it all away. Apollo hardware would be scrapped or sent to reside in museums.

As you read this on the 16th day of April 2012 the space shuttle Discovery is being prepared for its final flight, not into space, but on the back of a 747 carrier aircraft enroute to the National Air and Space Museum. Like Apollo, once again America has taken all that it had invested in the space shuttle and with barely a whimper from the American public who will in decades to come still be reaping the harvest of benefits from that program- we are simply casting it away to scrap or to reside in museums. Again we see an example of just how myopic we Americans remain. (Images provided by NASA)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (04.15.24)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (04.15.24) Classic Aero-TV: 'No Other Options' -- The Israeli Air Force's Danny Shapira

Classic Aero-TV: 'No Other Options' -- The Israeli Air Force's Danny Shapira Aero-News: Quote of the Day (04.15.24)

Aero-News: Quote of the Day (04.15.24) Airborne 04.16.24: RV Update, Affordable Flying Expo, Diamond Lil

Airborne 04.16.24: RV Update, Affordable Flying Expo, Diamond Lil ANN's Daily Aero-Term (04.16.24): Chart Supplement US

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (04.16.24): Chart Supplement US