Most Formed With Planets, Not As Result Of Collision

The next time you take a moonlit

stroll... or admire a full, bright-white moon looming in the night

sky... you might count yourself lucky, say astronomers at NASA's

Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

The next time you take a moonlit

stroll... or admire a full, bright-white moon looming in the night

sky... you might count yourself lucky, say astronomers at NASA's

Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

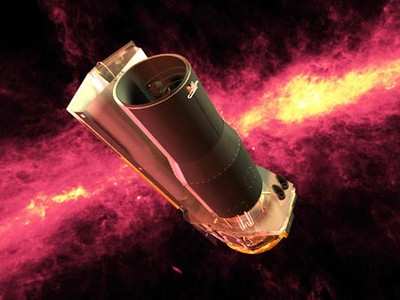

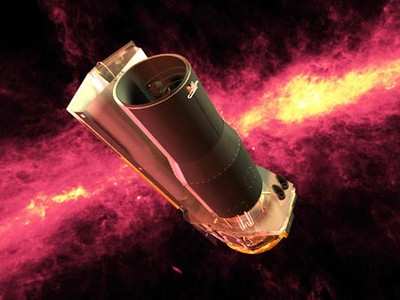

New observations from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope (shown

below) suggest moons like Earth's -- formed out of tremendous

collisions -- are uncommon in the universe, arising at most in only

five to 10 percent of planetary systems.

"When a moon forms from a violent collision, dust should be

blasted everywhere," said Nadya Gorlova of the University of

Florida, Gainesville, lead author of a new study that appeared last

week in the Astrophysical Journal. "If there were lots of moons

forming, we would have seen dust around lots of stars -- but we

didn't."

Scientists believe Earth's moon arose about 30 to 50 million

years after our sun was born, and after our rocky planets had begun

to take shape. A body as big as Mars is thought to have smacked

into an infant Earth, breaking off a piece of its mantle. Some of

the resulting debris fell into orbit around Earth, eventually

coalescing into the moon we see today. The other moons in our solar

system either formed simultaneously with their planet, or were

captured by their planet's gravity.

Gorlova and her colleagues looked for the dusty signs of similar

smash-ups around 400 stars that are all about 30 million years old

-- roughly the age of our sun when Earth's moon formed. They found

that only one out of the 400 stars is immersed in the telltale

dust. Taking into consideration the amount of time the dust should

stick around, and the age range at which moon-forming collisions

can occur, the scientists then calculated the probability of a

solar system making a moon like Earth's to be at most five to 10

percent.

"We don't know that the collision we witnessed around the one

star is definitely going to produce a moon, so moon-forming events

could be much less frequent than our calculation suggests," said

George Rieke of the University of Arizona, Tucson, a co-author of

the study.

In addition, the observations tell astronomers that the

planet-building process itself winds down by 30 million years after

a star is born. Like our moon, rocky planets are built up through

messy collisions that spray dust all around. Current thinking holds

that this process lasts from about 10 to 50 million years after a

star forms. The fact that Gorlova and her team found only 1 star

out of 400 with collision-generated dust indicates that the

30-million-year-old stars in the study have, for the most part,

finished making their planets.

"Astronomers have observed young stars with dust swirling around

them for more than 20 years now," said Gorlova. "But those stars

are usually so young that their dust could be left over from the

planet-formation process. The star we have found is older, at the

same age our sun was when it had finished making planets and the

Earth-moon system had just formed in a collision."

For moon lovers, the news isn't all bad. For one thing, moons

can form in different ways. And, even though the majority of rocky

planets in the universe might not have moons like Earth's,

astronomers believe there are billions of rocky planets out there.

Five to 10 percent of billions is still a lot of moons.

Other authors of the paper include: Zoltan Balog, James

Muzerolle, Kate Y. L. Su and Erick T. Young of the University of

Arizona, and Valentin D. Ivanov of the European Southern

Observatory, Chile.

Classic Aero-TV: The Switchblade Flying Car FLIES!

Classic Aero-TV: The Switchblade Flying Car FLIES! ANN FAQ: Q&A 101

ANN FAQ: Q&A 101 ANN's Daily Aero-Term (04.12.24): Discrete Code

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (04.12.24): Discrete Code ANN's Daily Aero-Term (04.13.24): Beyond Visual Line Of Sight (BVLOS)

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (04.13.24): Beyond Visual Line Of Sight (BVLOS) ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (04.13.24)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (04.13.24)