ANN Guest Editorial By Jerry Gregoire, Redbird Flight

Simulations

ANN E-I-C

Note: We LOVE guest editorials... especially

when we can learn so much from them. We particularly favor them

when they are gutsy, well-thought-out, controversial and brutally

honest. This one is all that... and more... and comes from a guy

whom we have observed to be one of those innovative personalities

that has no fear of coloring outside the lines and dares to do what

others insist can not or should not be done. I hope you enjoy this

piece as much as I did... and we greatly look forward to working

with Jerry

this March at the Aviation Transformation Conference

2012... as he was one of our earliest invitees. Issues

like those he brings up, and so many others, will be THE center of

attention at the forthcoming 2012 Aviation Transformation

Conference... an event designed to seek true Transformative Change

for the aviation world. -- Jim Campbell, ANN Editor-In-Chief (and

pleased to find out that I'm NOT the only troublemaker in GA --

GRIN).

ANN E-I-C

Note: We LOVE guest editorials... especially

when we can learn so much from them. We particularly favor them

when they are gutsy, well-thought-out, controversial and brutally

honest. This one is all that... and more... and comes from a guy

whom we have observed to be one of those innovative personalities

that has no fear of coloring outside the lines and dares to do what

others insist can not or should not be done. I hope you enjoy this

piece as much as I did... and we greatly look forward to working

with Jerry

this March at the Aviation Transformation Conference

2012... as he was one of our earliest invitees. Issues

like those he brings up, and so many others, will be THE center of

attention at the forthcoming 2012 Aviation Transformation

Conference... an event designed to seek true Transformative Change

for the aviation world. -- Jim Campbell, ANN Editor-In-Chief (and

pleased to find out that I'm NOT the only troublemaker in GA --

GRIN).

A couple of weeks ago I was flying

a brand new Citation CJ, single pilot with no passengers, thank

goodness, from Manassas to Jackson, Mississippi. My actual

destination was Austin, Texas but because the FAA doesn't allow

brand new airplanes to fly in RVSM airspace until an FAA inspector

has spent a few weeks staring at the Cessna issued RVSM book that

comes with every brand new airplane, I was burning an extra 100

gallons of Jet A per hour. I ought to tell Al Gore on these guys.

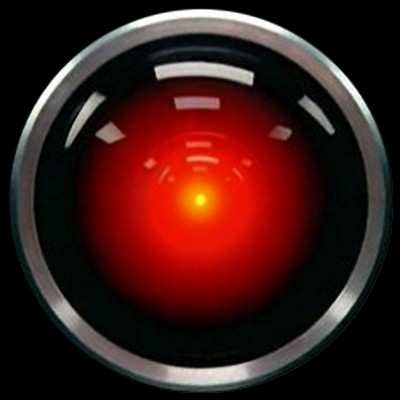

While in the cloud tops and chop at FL270, enjoying the "new

airplane" smell, I got a Master Warning with the associated red

lights and a screaming "RIGHT ENGINE OIL PRESSURE" aural warning

loud enough for Helen Keller to hear. This was a first for me

… in the real CJ, anyway.

A couple of weeks ago I was flying

a brand new Citation CJ, single pilot with no passengers, thank

goodness, from Manassas to Jackson, Mississippi. My actual

destination was Austin, Texas but because the FAA doesn't allow

brand new airplanes to fly in RVSM airspace until an FAA inspector

has spent a few weeks staring at the Cessna issued RVSM book that

comes with every brand new airplane, I was burning an extra 100

gallons of Jet A per hour. I ought to tell Al Gore on these guys.

While in the cloud tops and chop at FL270, enjoying the "new

airplane" smell, I got a Master Warning with the associated red

lights and a screaming "RIGHT ENGINE OIL PRESSURE" aural warning

loud enough for Helen Keller to hear. This was a first for me

… in the real CJ, anyway.

Master Warnings in this airplane come in five flavors, those

being engine fire, cabin pressure, battery over-temp, a dual

generator failure, and oil pressure (or lack thereof) and they are

as rare as two dollar avgas. When they do happen, though, you need

to do something pretty quick.

So, here's the scene: red lights on the panel, a concentration

killing aural warning that I can't shut off, for some reason, and a

list of memory items in my head that may or may not be the right

list of memory items for this problem. With so many opportunities

to do the wrong thing, many of which could cause an even bigger

problem, I was fortunate to have practiced this a hundred times

before in a simulator.

Remember Zeno's Paradox? In case you don't, it's a mathematical

absurdity that goes: If you travel from point A to point B, you

necessarily must travel half way to point B before traveling all of

the distance. Now from that point, you must again travel half of

the remaining distance. If you continue to do so (always traveling

half the distance), how could you ever hope to reach point B?

The fact that we do, on occasion, reach point B is, in a very

roundabout way, proof that some mysteries are not mysteries at all.

They are simply a failure to correctly frame the question, a

question based on a faulty and provably untrue supposition.

Along those same lines, a lot of very troubling data has come

out lately on the state of flight training indicating fewer and

fewer new student enrollments, a stunning 78% drop out rate before

the check ride, and, in spite of more regulations, more chapters in

the training manuals, and more technology in the cockpit, accident

rates that stubbornly refuse to go down. Now, armed with this

information, try this little experiment. Call every flight school

owner or general manager you know and ask them what it is they

think they need to change about THEIR particular training program

to address this issue. I can guarantee that every single one of

them will say,

"Well, .... (shrug) .. nothing. If there was anything that we

needed to change we would have changed it by now".

Nothing? You mean …. nothing? How can the answer be,

"Nothing"?

It's because the question is based on the false notion that

flight training and, in particular, flight schools are to blame for

this problem. For the most part, they are not to blame. So, who is,

you ask? Well, if your company or organization builds airplanes, or

writes regulations, or services airplanes, or writes curriculums,

or sells insurance, or sells pilot supplies, or manages airports,

or sells fuel, or runs airport security, or advocates for pilots,

or builds flight simulators then YOU are probably to blame for this

problem and, just as probably, YOU are not doing enough about it.

That's a real shame because your company will be one that

ultimately suffers.

Author's Note: If you were insulted to

the point of violence by the preceding remark, it might be best to

quit reading now. I've always believed that before you criticize

someone, you should first walk a mile in their shoes. That way,

when you do criticize them, you'll be a mile away, and you'll

have their shoes.

This dedicated in-activism in support of the single most

important driver of general aviation's future is a certified

mystery. Strange, short-sided, suicidal behavior on an

industry-wide scale. Fixable? Yes, but not until we stop pointing

the finger at the flight school operators and start coming to grips

with our individual and collective lack of investment in this

regard.

A friend sent me an article he'd clipped from the Christian

Science Monitor a while back that said something about how

wonderful Stanley Kubrick's movie 2001: A Space Odyssey was and how

it still resonates some 40+ years later. Nonsense. A tiny article

on the back of the clipping, however, did catch my eye. It told of

a 25 watt light bulb that had been burning continuously for the

past 70 years in the restroom of an Ipswich, England electric shop.

The story isn't so remarkable because of this single, perversely

persistent, light bulb but because this particular bit of

technology made, 70 years ago, is still compatible with 21st

century systems. It's a reminder that things in their

quintessential form-be they technology, processes or even ideas-if

left unmolested, can and do last a very long time. And furthermore,

despite the hype, real, honest-to-God, life-altering, bell-ringing

change has actually been decelerating when viewed over a period of,

say 100 to 120 years. The fact is, the gadgets that fill our homes

and mount in our cockpits are merely the sheen of technology, and

our boasts of rapid and miraculous change are actually little more

than the narcissism of small differences.

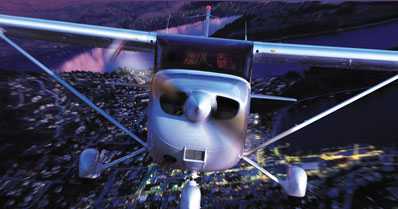

Airplanes fly the way they used to 70 years ago. They still have

propellers for thrust, wings for lift, and an unusable whiskey

compasses flopping around during turns for navigation. Everything

truly new in the last 70 years has been done in the pursuit of

safety. Safety is good, but most of what has been done, as the

statistics show, is sugar sprinkles on a birthday cake. There's

technology that keeps a pilot better informed and more distracted

at exactly the same time, volumes of new and conflicting

regulations, and well meaning yet worthless additions to the

required curriculums.

By the way, does anyone out there think that CRM training for

single pilot operations or memorizing the five hazardous attitudes

of pilots is making a dent? It's like they say, you have to have at

least three of the hazardous attitudes just to climb into a

cockpit.

Our fixation on layering complexity in the name of flight safety

is a conditioned response to deal with the ever larger and more

complicated challenge of flying completely risk free. It is, as

Descartes would say, to doubt what isn't self-evident and reduce

every problem to its simplest component. In the face of greater

complexity, we are forced to concentrate more and more about less

and less and pursue solutions that are split into sub-disciplines

and sub-sub-disciplines and pared down to pinpoints. Complexity

breeds complexity.

That the process of flight training has completely jumped the

rails is certain. Pinpointing exactly when this happened is not. A

close, but misguided, friend of mine who is usually right in all

things aviation, believes that flight schools started falling

behind and falling apart when technology took over in the cockpit

and in aviation in general. In his estimation, the rest of the

aviation industry has been moving away from the flight training

industry for, at least, the last 15 years.

Silly pilot.

Everyone, with the possible exception of the luddites at the

FAA, would agree that the aviation industry is not known as an

early, or even a timely adopter of technology. I still cringe when

I think about the excitement "touch screens" generated at this most

recent Sun 'N Fun. It was as if aviation had just discovered the

dipstick. Jeeez. Touch screens have been around since 1971! There

are touch screens on the gas pumps at the Git-'N-Go. The fact is,

aviation is the last adopter of technology and, for the most part,

adopt new technology only under some kind of duress. And when it

does finally deliver this or that technology, it's certainly not a

surprise to anyone. No one, including the flight training industry,

is caught off guard.

To our collective shame, our industry did not move away from

flight training, it turned away.

So much blame to slather around and so little time.

Let's spare the minor players and concentrate on the Four

Horsemen of this particular Apocalypse,

- The Airplane Manufacturers,

- The Avionics Manufacturers,

- the FAA,

- And The Simulator Manufacturers.

On that list of things one doesn't talk about in polite company

like sex, politics, and, of course, Fight Club, a criticism of the

aviation industry coming from within will not be welcome.

Politeness was what killed the dinosaurs.

When the master warning went off in the cockpit, the second

biggest surprise, after the fact that it went off at all, was how

incredibly loud the aural warning was. I've since come to learn

that the volume is not determined by the manufacturer, but by the

FAA during certification. While it's certainly important that the

pilot and co-pilot hear the warning and, perhaps, it's important

for the passengers to here it, although I can't imagine why, must

it be loud enough for the guys in the next airplane? In any case,

once the aural alarm sounds, you're supposed to be able to turn it

off by pressing the Master Warning button on the panel.

Unfortunately, that wasn't working, no matter how many times I

pressed it. Concentrating on the emergency was a first class

challenge and it became an even bigger problem later when I

attempted to contact ATC.

Abandoning any hope of recalling the memory items, I reached for

the emergency checklist and began thumbing for the correct tab.

Even reading comprehension was an issue with this screaming going

on. Imagine trying to read a physics textbook in a room that's on

fire while a rabid monkey shoves an ice pick in your ear and you've

got a pretty good idea where my concentration was. Slowing my brain

down enough to focus was the first order of business. Rehearsing so

many drills like this in the simulator taught me a very important

thing about emergencies in a CJ, that is, that as long as the

airplane is still flying and nothing appears to be on fire, you've

got time. And while the first thing that pops into your head might

be the right thing, it's far better to wait to see if that's the

second thing that pops into your head.

I finally found my place in the checklist and, by this time,

began to suspect that the problem was a false indication.

There are few manufactured products that I can think of that

have not improved in their value proposition, over time. By that I

mean, there are few machines that, over time, have not gotten

significantly less expensive, like computers, or delivered more

features and capability for the same money (adjusted for

inflation), like cars. Adjusted for inflation, the cost of the

average car is about the same today as it was in 1960.

In 1960 a new Cessna 172 cost $9,000.00, which would be

$66,000.00 in today's dollars. In 2011, a new Cessna 172 actually

costs a heart stopping $300,000.00. Cessna has had fifty years to

figure out how to apply the fundamentals of automation to the

manufacture of this airplane, and they're still building them like

they're not quite sure how they go together. As value propositions

go, it doesn't get much worse than this. So, why does Cessna chose

to continue to operate this way? Because, while they may have

competition, no one is doing it any better. Among the short list of

battle tested, widely available, easily supportable, VFR/IFR flight

training platforms, the Piper Warrior, a Diamond DA40, and the

Cirrus SR22 sell for between $300 and $420 thousand dollars.

About this time, you're probable saying to yourself, "What about

the LSA's like the Skycatcher or the Remos?". To which, I would

answer, "Read this paragraph more carefully".

Add in all of the wonderful features that Cessna has added to

the 172 like a bigger, better engine, better avionics, leather

seats with those nice little folds, better ventilation, and high

performance cup holders and you still can't justify or even explain

that cost. Cessna will, no doubt, tell you that the real cost

increases are due to the complexities of certification, and that

might be true, except that we're talking about an airplane that was

certified in 1958. If they spent all of that money certifying

changes in cosmetics, they shouldn't have.

No matter how you cut it, an aircraft with a $300,000.00 price

tag, regardless of the quality of its cup holders, is not well

suited for the mission of most flight schools. If Cessna offered a

brand new 1960 172 with exactly the same features and capabilities

of their 1960 model, would you buy one for $66,000.00? How about at

twice that price? I would and so would every flight school in the

world.

Modern aircraft avionics, aka glass cockpits, are magic. In the

hands of a well trained pilot, they make flying safer and easier

and give our aircraft a whole new level of utility. Because of

their spectacular breadth of functionality, the operation is not

always intuitive and students have to be carefully trained to avoid

the distraction of trying to figure out how to load a STAR while

flying the airplane. The very best and safest place to train a

pilot in the use of these devices is in a flight simulator,

operating in the context of an actual (simulated) flight, instead

of simply using a computer-based tutorial or, worse, just reading

the manual. Up until the arrival of Redbird, flight simulators that

had glass cockpits were extremely expensive because the avionics

manufacturers charge the simulator manufacturers same price for

their equipment as they charge the aircraft manufactures, which is

….. a lot. This was, before Redbird, a huge barrier for most

flight schools wishing to provide 'glass cockpit' training.

Redbird's approach to reducing those costs was to replicate the

functionality of, for instance, the Garmin G1000 using home-grown

software and standard displays with correctly positioned keys and

buttons. This brought the cost of a glass cockpit simulator down

from $95 thousand to just $8 thousand. It also irritated the hell

out of the avionics manufacturers. Well, …. that's tough, as

far as we're concerned. Perhaps they should have been giving the

simulator companies a meaningful price break in the name of flight

safety.

At a conference recently, I overheard an executive from one of

these avionics companies telling someone else that their new line

of touch screen devices would be impossible for Redbird to

replicate. That's so stupid, it makes my hair hurt. Was he

bragging? Was this guy irresponsible enough to believe that driving

the cost of flight training back up was a good thing? Was he

delusional enough to think Redbird couldn't adapt "touch screen"

technology to their simulators? Hell, we've already done it!

The FAA's mission statement, taken directly from the website

reads:

"Our continuing mission is to provide the safest, most efficient

aerospace system in the world."

Good mission. I particularly like the fact that it says "safest"

and not "safe". It's a recognition that "safe" is unattainable

until the day comes when we are no longer allowed to fly our

airplanes.

The FAA is a regulatory agency. A regulatory agency writes

regulations for a living. For every regulation, good or bad,

necessary or unnecessary, the target if those regulations,

companies and individual pilots, pay a price in cash and

productivity. Those additional costs are not the FAA's problem. The

FAA balances safety and security against cost, productivity, and

freedom on a rusty, frozen scale.

According to a Gallup poll from a couple of years ago, 18% of

Americans are under the impression that the Sun orbits around the

Earth. That's approximately 50 million Americans. Given the sheer

size of this number, might we expect that some of these folks are

currently writing regulations for the rest of us?

Up until recently flight simulators for universities and

small-to-medium sized flight schools fell into one of two extreme

categories, one being simulators that were far too expensive for a

normal flight school to afford and the other being simulators,

those certified as Advanced Aircraft Training Devices (AATD), that

were far too useless for ab initio training. Simulator design,

driven entirely by the certification demands of the FAA and their

amazing grasp of 1950s technology, gave AATD certification credit

exclusively to designs addressing instrument training while

ignoring the needs of entry level students. The implication is that

training for new students, you know, the ones with no skills, was

best handled in the airplane. After all, what could possibly go

wrong?

Even today, when we certify a simulator as an AATD there is no

additional credit given for features critical to training beginner

students such as wrap around visuals to teach VFR maneuvers,

accurate representations of the terrain between the airports to

teach pilotage and cross country skills, or even motion to train

airplane handling skills. As far as the FAA is concerned, a full

motion simulator with wrap around (sideways looking) visuals,

accurately placed avionics controls, and a world-wide data base of

airports and terrain is no more valuable than a simple desktop sim

with a single 12 inch monitor.

In 2006 a partner of mine and I had just finished a check ride

in a Level D King Air sim, a machine that costs somewhere North of

seven million dollars. We had had some difficulty flying a circle

to land approach because the visuals were so bad. They were hazy,

uneven in intensity and color and lacked detail. As we climbed out

of that overpriced cement mixer, we had one of those moments when

we realized that given the state of technology, we could easily

design a visual system that was far better than this one at a tiny

fraction of the cost. Pretty strange. We wondered, if we knew how

to do it, why weren't the big guys, or even the small guys,

building simulators that had decent, affordable visuals. The

answer, sadly, has to do with the momentum that keeps companies and

industries stuck in old paradigms combined with a fundamental

misunderstanding of the marketplace and its needs.

A few computer-geek companies from outside the industry, Redbird

included, could see the potential of applying off-the-shelf and

emerging technologies to the problem of providing affordable,

functional simulator solutions. Redbird made the critical decision

to break with the FAA's point of view on what makes a adequate

training device and started building simulators that are designed

to go beyond minimum certification requirements. Their goal was a

widely affordable IFR/VFR trainer to make safe, proficient pilots

in a predicable, safe environment. The introduction of the Redbird

FMX exposed a huge underserved market with enormous untapped

potential and the resulting sales have been simply amazing. Imagine

Redbird's surprise when the demand for a fully capable VFR trainer

seemed to magically appear. To give you some idea of the size of

the demand, 170 full motion Redbird simulators have been delivered

in the last 24 months.

Does that sound like bragging? Maybe, but 170 full motion flight

simulators is more than anyone has ever sold over any period of

time. It is also less than 5% of the available market. Lots more

work to do.

As successful as Redbird has been in creating and exploiting

this new market, I consider Redbird's efforts, to date, to be

wholly inadequate. Like the rest of the industry, Redbird has not

done a good enough job developing the curriculums or process

guidance many schools need to get maximum benefit from the

simulators they buy. Further, simulator companies need to do more

to make their devices more accessible to students as skills

trainers, and finally, they need to find better ways to efficiently

develop the most relevant designs possible. The fact is, from a

design standpoint, we are often shooting in the dark. Under the

current circumstances, we are all forced to design a system and

measure its effectiveness not based on some objective measurement

of student performance, but by whether it sells well or not. This

is a very inefficient way to design things.

Consider the question: Does motion help in ab initio training?

We think it does. There seems to be a lot of anecdotal evidence

supporting that notion but, we can't prove it. Our competition, the

ones that do not have a line of motion simulators, likes to say it

doesn't help. I might say that too, if I had to compete with

Redbird.

About a year ago Redbird decided they needed to understand the

effect of motion and other design features in a more systematic and

measurable way. They approached several well known universities

with large flight programs for help. Redbird offered simulators and

support for use in training, in order to allow those schools, with

their large student populations, to measure the results in a way

that would help everyone involved build better systems. Redbird's

proposal to the schools was met with a collective yawn or something

a little more rude than that. While the lack of intellectual

curiosity among these institutions might have been a surprise,

their unwillingness to engage their public institutions in efforts

that were fundamental to their charter as research and learning

institutions, was deeply disappointing.

To underline the challenge we all face in determining how to

best design and utilize simulation in training, we have come to

understand that flight simulators in their present form are

primitive and inadequate. Companies that only manufacture

simulators for a living will surely disappear and very soon. What

is missing in our current designs is the true and certain future

role of the simulator not just as a training tool, but as a

training delivery system. Our current simulator designs are also

inadequate because of our industry's insistence on delivering

training, not at the convenience and the optimal pace of the

student, but based on the availability of the instructor. This is

crazy stupid and given the state of the technology, completely

unnecessary...

Step one on the checklist for an oil pressure Master Warning

is to check the other indications. Everything else looked fine: oil

pressure indication was green as was the oil temperature, N1 and N2

normal, airplane flying straight. Step two was to pull back the

power on the affected engine to idle to see if there was "slight"

movement in the oil pressure indication. Slight? There was, I

guess. Step three, leave the affected engine at idle and land as

soon as practical. I was 20 minutes out of Jackson, my filed

destination, and completely out of range of the closest Citation

Service Center, so Jackson it was.

Single engine flight at cruise is not much of an event in a CJ,

particularly once you start a descent and you've pulled the other

engine back. My biggest problem right now was trying to communicate

with ATC while the aural warning was going on in the background.

The difficulty understanding ATC and being understood was creating

its own hazard. My safety equipment was making the flight unsafe.

Every new contact I made with ATC, no matter what I asked for, was

followed with the question, "Do you wish to declare an emergency?"

So why, you wonder, didn't I just pull the circuit breaker on the

warning system? Have you ever left home without your wallet?

On final into Jackson, I brought the right engine back up out of

idle to make the landing easier, slid the airplane on to the runway

nicely, rolled off onto the taxiway and called Jackson ground for

taxi clearance.

"Do you wish to declare an emergency?", they answered.

I think about this event, a non-emergency emergency caused by a

faulty switch, pretty often. I could have easily turned this

non-event into a real emergency had I not been conditioned by the

training I've received in a flight simulator.

It turned out that the reason I couldn't turn off the aural

warning was because the little oil pressure switch on the engine

was failing and then working and then failing and then working

again every one or two seconds. A little switch on a new airplane.

A little $885 switch, just like the $12 ones they have in cars,

attached to the idiot light on the dashboard. When was the last

time you had one fail in your car?

Lacking a solution for effectively testing our designs and

efficiently developing new ones we have committed to building an

R&D facility in the form of a working, for profit, flight

school at an airport in central Texas. The work product of that

institution will be available to and benefit everyone in the

industry and we, and our development partners, are looking forward

with great anticipation to its opening in the fall of 2011. As a

step toward fixing the problems with flight training, it's a drop

in the bucket, but it's a start.

But what about everyone else, the airplane manufacturers, the

avionics companies, the insurance companies, the regulators, and so

on? What are you guys going to do to help save flight training?

Here's an idea. How about establishing flight training as a

separate "class" of customer with its own special products,

pricing, and services. Yes, special pricing does mean reducing your

prices. This strategy is used all the time by all kinds of

industries to promote future business. Microsoft does it for

students and teachers, country clubs offer junior memberships, car

companies do it for graduates in the name of establishing a future

customer on a particular product track. Think of this as a

marketing cost, an investment for future returns.

A risky move? Maybe, but doing nothing is riskier.

Should you wait until the other guy does something first?

Ask our competitors how that idea worked out for them.

Note: Jerry Gregoire is the Founder and

Chairman of Redbird Flight Simulations and is a member of

the General Aviation Manufacturers Association (GAMA) Board of

Directors. He's also a heck of an interesting guy to talk to...

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (04.15.24)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (04.15.24) Classic Aero-TV: 'No Other Options' -- The Israeli Air Force's Danny Shapira

Classic Aero-TV: 'No Other Options' -- The Israeli Air Force's Danny Shapira Aero-News: Quote of the Day (04.15.24)

Aero-News: Quote of the Day (04.15.24) Airborne 04.16.24: RV Update, Affordable Flying Expo, Diamond Lil

Airborne 04.16.24: RV Update, Affordable Flying Expo, Diamond Lil ANN's Daily Aero-Term (04.16.24): Chart Supplement US

ANN's Daily Aero-Term (04.16.24): Chart Supplement US