Sun, Mar 23, 2014

May Also Reduce Fuel Consumption

Researchers at University West in Sweden have started using nanoparticles in the heat-insulating surface layer that protects aircraft engines from heat. In tests, this increased the service life of the coating by 300%. This is something that interests the aircraft industry to a very great degree, and the hope is that motors with the new layers will be in production within two years.

To increase the service life of aircraft engines, a heat-insulating surface layer is sprayed on top of the metal components. Thanks to this extra layer, the engine is shielded from heat. The temperature can also be raised, which leads to increased efficiency, reduced emissions, and decreased fuel consumption.

The goal of the University West research group is to be able to control the structure of the surface layer in order to increase its service life and insulating capability. They have used different materials in their work. "The base is a ceramic powder, but we have also tested adding plastic to generate pores that make the material more elastic," says Nicholas Curry, who has just presented his doctoral thesis on the subject.

The ceramic layer is subjected to great stress when the enormous changes in temperature make the material alternately expand and contract. Making the layer elastic is therefore important. Over the last few years, the researchers have focused on further refining the microstructure, all so that the layer will be of interest for the industry to use. "We have tested the use of a layer that is formed from nanoparticles. The particles are so fine that we aren't able to spray the powder directly onto a surface. Instead, we first mix the powder with a liquid that is then sprayed. This is called suspension plasma spray application.

Dr Curry and his colleagues have since tested the new layer thousands of times in what are known as "thermal shock tests" to simulate the temperature changes in an aircraft engine. It has turned out that the new coating layer lasts at least three times as long as a conventional layer while it has low heat conduction abilities. "An aircraft motor that lasts longer does not need to undergo expensive, time-consuming "service" as often; this saves the aircraft industry money. The new technology is also significantly cheaper than the conventional technology, which means that more businesses will be able to purchase the equipment.

Research at University West is conducted in close collaboration with aircraft engine manufacturer GKN Aerospace (formerly Volvo Aero) and Siemens Industrial Turbomachinery, which makes gas turbines. The idea is that the new layer will be used in both aircraft engines and gas turbines within two years.

One of the most important issues for the researchers to solve is how they can monitor what happens to the structure of the coating over time, and to understand how the microstructure in the layer works. "A conventional surface layer looks like a sandwich, with layer upon layer. The surface layer we produce with the new method can be compared more to standing columns. This makes the layer more flexible and easier to monitor. And it adheres to the metal, regardless of whether the surface is completely smooth or not. The most important thing is not the material itself, but how porous it is," Dr. Curry says.

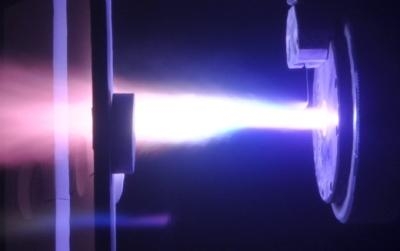

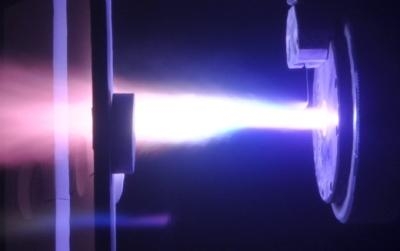

The surface layers on aircraft engine and gas turbines are called the thermal barrier coating and they are manufactured using a method called thermal spray application. A ceramic powder is sprayed onto a surface at a very high temperature–7,000 to 8,000 degrees C–using a plasma stream. The ceramic particles melt and strike the surface, where they form a protective layer that is approximately half a millimeter thick.

(Image provided by University West)

More News

Inversion to Launch Reentry Vehicle Demonstrator Aboard SpaceX Falcon 9 This fall, the aerospace startup Inversion is set to launch its Ray reentry demonstrator capsule aboard Spac>[...]

"We are excited to accelerate the adoption of electric aviation technology and further our journey towards a sustainable future. The agreement with magniX underscores our commitmen>[...]

"The journey to this achievement started nearly a decade ago when a freshly commissioned Gentry, driven by a fascination with new technologies and a desire to contribute significan>[...]

Aero Linx: OX5 Aviation Pioneers Each year a national reunion of OX5 Aviation Pioneers is hosted by one of the Wings in the organization. The reunions attract much attention as man>[...]

"Our driven and innovative team of military and civilian Airmen delivers combat power daily, ensuring our nation is ready today and tomorrow." Source: General Duke Richardson, AFMC>[...]

SpaceX to Launch Inversion RAY Reentry Vehicle in Fall

SpaceX to Launch Inversion RAY Reentry Vehicle in Fall Aero-News: Quote of the Day (04.23.24)

Aero-News: Quote of the Day (04.23.24) Aero-News: Quote of the Day (04.20.24)

Aero-News: Quote of the Day (04.20.24) ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (04.20.24)

ANN's Daily Aero-Linx (04.20.24) Aero-News: Quote of the Day (04.21.24)

Aero-News: Quote of the Day (04.21.24)